Grandad – the lost autobiography.

Sometime in the mid 1970s my Grandad – William George Arnold – wrote his autobiography for me in two tiny notebooks. I have kept them in my archives for decades. I finally decided it was time to type them up and post them on my website, if only for other family members to read.

I cannot find them. They have disappeared. Vanished. Gone.

I have turned out the archives, I have emptied my office cupboards and my desk drawers, I have searched through my bookshelves – as well as behind them. Nothing. I have asked around the family – Did I lend them to anyone ? No.

I have now had to accept that they are gone, that I have – somehow – lost these precious records – lost my Grandad’s life.

I must save what I can. This is my attempt to recall and record what I remember of what he wrote.

*

He began by saying that he was writing this autobiography because he felt that his grandson might have some journalistic leanings. I think he also enjoyed – in his 70s – the opportunity to recall his past, his adventures and his family.

He was born in 1900 in Beckenham, Kent. His father, Albert Edward Arnold, was a builder’s labourer and his mother, Rosina Aylin, had almost certainly been a housemaid before her marriage, as was customary for most young girls at this time. They had seven children, Grandad being the second. Although he was christened William he was always known by his second name, George. The family were not well off. Like others of their position, they lived in rented rooms. They had to move more than once just ahead of the arrival of the bailiffs. As a boy, Grandad had on one occasion been very ill. His mother sat up with him during the night and in her distress accidently gave him a dose of alcohol – gin perhaps – instead of his medicine. This is what saved him he claimed.

In 1917/18 Grandad lied about his age and was about to join the Royal Flying Corps. To his great disappointment, the war ended and his services were no longer required.

Grandad’s working life was spent entirely with motor vehicles – cars, vans and lorries. One of his early jobs was driving the delivery van for a baker’s firm in Purley, a few miles from Beckenham. It was here that he met my Grandma, Louie Ada Hosier. He fell in love with her voice. She was working in the accounts office and he somehow overheard her speaking before he actually saw her. They were married in 1925 in Chipstead Valley, Coulsdon, where my Grandma’s family lived.

Grandad worked for many years as chauffeur to a wealthy journalist, Mr Hartley Aspden, CBE. Granddad seems to have been much appreciated by Mr Aspden and his family. He kept up with Miss Kathleen, a daughter of the house, into his retirement and I believe it was she who helped Grandad purchase a private car hire business in the 1950s, Harmer Hire Cars, based at Smitham Station in Coulsdon. It may also have been during his time as a chauffeur that Grandad bought the family’s first house, in Manor Way, Woodmansterne.

Grandad also went to war. Having been too young for the First World War he was now too old to be called up for the Second. Therefore, in 1944 or thereabouts, he volunteered – not wishing to miss the chance of adventure yet again. He joined the army as a lorry driver and carried supplies to the allied forces following D-day and the re-occupation of France, Germany and Scandinavia. (I gather that this unnecessary disappearance at a time of general wartime hardship for the family was not entirely welcomed. He did not mention this in his writings).

The missing note books contain the details of the route his unit took and the villages and towns they visited or passed through. I particularly regret that I cannot now reconstruct his great adventure and relate it to the history in which he enjoyed – it seems – a small part. The only tales I recall is that he drove his lorry across a Norwegian Fiord on the hull of an up-turned, half sunk ship – and he witnessed the aurora borealis. He later received an official thank you certificate for his contribution to the liberation of Norway from King Haakon VII, which I have in my archives.

The car hire business did not go so well and after a few years he sold it and became a taxi driver based at a rank in Coulsdon. He and Grandma had also moved to a new house on Hartley Hill in Purley. I remember his black Austen taxi, with its open luggage compartment beside the driver’s seat (in which he once let me ride) and fold-down seats in the back. We used to go to the south coast in it for the day. I would get car sick. Later he replaced it with the then new design of London taxi.

Grandad had always had access to cars and would take his family on holiday to the West Country and elsewhere in Britain both before and after the war. In 1965 he bought a black and white Triumph Herald which he kept on the road until he finally gave up driving in the 1980s. By this time Granddad and Grandma had retired to Westergate, just north of Bognor – one of the sea-side towns we visited in his taxi when I was a child.

Grandad died in 1985, when I was living in India.

I had already said goodbye to him before I left.

*

Having written the above – and after some time – I inadvertently found Grandad’s original notebooks ‘filed’ in some completely random place in my archive. I was overjoyed ! I typed them up a once and now here they are below.

What strikes me most about Grandad’s autobiography is how appalling the situation of his family was in his childhood, and how far he had come by the time I knew him. Of course this is a tale that could be told of many such families and individuals over this period. It was a time of great social and economic change. It’s a pity it took two World Wars to make the change. I am also struck by the fact that when he was born, the infernal combustion engine – with which he was involved for most of his life – and the aeroplane, had only recently been invented. By the time he left us, persons had landed on the moon and you could get from London to New York by Concorde in three hours. Well, some folk could.

William George Arnold (1900 – 1985) – Autobiography.

I do not anticipate that anyone other than my grandson Kevan will be interested in the following chronicle of my 70 years. Kevan thinks the that I have had an interesting life though I myself cannot lay claim to any great achievements or lay claim to any virtue that won a place to my credit. However, as I believe that he has some leanings towards journalism I will try to humour him, at least until I get tired, and leave it to him to weave my scribble and mistakes into a story, though what use he can make of it I can’t imagine. My part of the work will be notable for misspelling and incorrect punctuation etc., But Kevan of course with his first-class intellect will be able to remedy my errors.

I was born on June 12, 1900, the second son, or so I’m told, I have no recollection of the event. Times were hard for ordinary working people in those days, work was scarce and money more so. We lived in Penge, now it is part of London, and occupied the upper floor of a house in Rayleigh Road. Nothing much happened until I went to school at Alexandra Road. At this school we had a very severe head- mistress who was very fond of wielding the cane and I always went in mortal fear of her. On our way to school we usually saw a man delivering milk from a float. This was a three wheeled Barrow with a churn standing on it and a tap fitted so that the milk-man could fill his large can and carry it to each house where he would dip in his measuring can and pour into the customer’s jug. I was fascinated by this tap and one day I turned it on and ran away, leaving the milk flowing over the road. The next day I was scared to pass the milk float in case the man caught me, but I could not get to school without passing and so I hung back fearful and crying because I was getting late. Who should come along but the ogre our headmistress who wanted to know if what the trouble was. I had to tell her the truth, I can’t remember what she said to me, I believe she spoke to the milk-man and made my peace, afterwards escorting me to school – and I did not get a whacking.

It was at school that it was discovered that my sight was defective and this necessitated a weekly journey to the royal eye hospital, Elephant and Castle, for treatment. I found these excursions were interesting, though the hospital part was boring. We travelled on the tram-cars pulled by horses. Usually a pair of horses was sufficient as the rails made the going easy. It was all horse traffic in those days and the Elephant was a very busy junction, as indeed it is today, only more so. On these expeditions a few coppers would provide us with a basin of soup or a slice of and bread and dripping at one of the many coffee shops. The public houses seemed to be open all day and were the cause of much distress and broken homes as men and women took their hard-earned money to the brewers and sought to drown their sorrows in intoxicating liquor, causing them to forget for a while the hardship of life.

At home things began to go wrong, though as a child I did not know why. At first we missed the sweets we usually had given to us on Sunday. Then it was lack of food. I can remember as a child clinging to my mother’s skirts and crying for food while she, poor dear, cried because she had nothing to give us. On occasions like this, which seemed to become more and more frequent, my mother took us to an aunt or to our grandmother’s, dear old soul, and they filled our bellies. Both grandma and grandad seemed very old to us then, they were a dear old couple and were always very kind to us children They lived to a good old age and I have only very happy memories of them.

Christmas was always a wonderful time at my grandparents. They had a three-storey house at Beckenham. Two of their married children occupied rooms in this house and two of my aunt’s, who were not married, lived there as well. I remember the huge joint turning on a spit in front of the open fire, the cured hams hanging in odd corners and the barrel of ale. This was a beverage more in use than tea in those days but is a custom now died out.

Of after a while we moved from Penge to a flat in Beckenham. This was necessary as the family seemed to be growing and outstripping the accommodation. Our rent due at this abode was more than we could afford, 12 shillings a week I believe, and my mother found it necessary to seek employment. She went to work at a laundry from nine o’clock in the morning to nine at night. She received three shillings. My father, if he was lucky enough to have work, [was] paid at the most eight pence an hour. He was a very good workman and a strong trade unionist. I think now, when I look back, that he became discouraged with the battle to earn a living, he took to drink and at times he brought no money home to feed his constantly increasing family, thus creating the very heavy burden for my mother. We had to give up the flat of course and seek cheaper accommodation, but before we go on I must relate one little incident.

A railway went behind our house and we could climb the fence onto it. This we did one day and after placing some bricks on the rail waited for the train to come along and crash. Imagine our disappointment when the train simply swept the line clear of our obstructions.

Our next address took us a bit nearer to our grandma’s and from this time we seemed to be constantly on the move from one house to another. We never moved very far and mostly at night to avoid the landlord as we were apparently well in his debt. Things seemed to go from bad to worse, one or another of the family would be ill. I remember when we only had one of ? ? Eldest sister was in bed with diphtheria and the rest of us had measles together. We all managed to survive. Despite the hardships of life, I don’t think we children worried an awful lot. We were born to be poor and to be hungry. On the school holidays we ran about with bare feet, searching refuse heaps for anything we could sell to the rag and bone merchant for a few coppers, always scheming to get food by any means, honest or not.

If I never did any good at school, had I been well fed and clothed I could have done as well as anyone. I sat at my desk dreaming of lovely jam rolls and a tap flowing with milk. Today the children have milk at school. My mother was always receiving bills from the local tradesmen for goods – food of course – that we had obtained by pledging her credit. The shop got wise to us before long and my mother ceased to receive bills, while we remained hungry. I remember one occasion when us boys decided that the one and only chicken belonging to the man next door must die to provide us with a meal. How we were to prepare and cook this bird we never stopped to consider. We caught the chicken, stuffed it down the lavatory pan had pulled the chain, hoping to drown it. That chicken fought for its life and all we were left with were a few feathers. Very soon afterwards the owner of that chicken committed suicide but I don’t think we were the cause of that. We encountered death on another occasion when a man was found lying dead in a disused brick field nearby. When we arrived, a policeman had placed a handkerchief over the man’s face but we could see the revolver he had used in his hand.

Shops remained open all hours in those days and I remember we boys sitting as quiet as mice waiting for my mother to return home with her few shillings. Meanwhile father puffed steadily at his old vile-smelling clay pipe, filling the room with tobacco smoke. When mother came in we would be sent to the shops to buy the necessities of life and I remember being so dopey with sleep when I reached the shop I failed to remember what I was supposed to buy. One way of raising money for those days was to take anything of value to the pawnshop or Uncle Charlies’, as he was commonly called. There the article would be pledged for a fraction of its real value and redeemed by paying exorbitant interest. Failure to redeem left the pawnbroker free to sell the goods at a profit – altogether a good business for the pawnbroker but now practically a non-existent profession.

I was nearly 11 years of age when I went down with sunstroke and pneumonia and I can remember my father carrying me upstairs to bed where I remained between life and death for six weeks. I’d lost completely the power of speech and as I recovered I had the utmost difficulty in making known my wants. I had my 11th birthday in bed and King George the fifth was crowned as I lay ill. Prayers for my recovery was said in the local churches and were answered in a peculiar manner. The Doctor had just warned my mother that I had only a few hours to live. In an effort to do all she could to avoid this catastrophe she poured a generous dose of – as she thought -medicine down my throat. She had picked up the wrong bottle and given me methylated spirit. Actually, this revived me so that I struggled and gasped and the crisis was safely past. I was a weakling for months after, being wheeled about in a bath chair. Eventually someone from the church arranged for me to go to a convalescent home at Clacton-on- Sea where I stayed for two weeks, rather sick all the time.

I returned home to more trouble. The family had been turned out of the house on account of rent arrears. My mother and family had been taken to the work house, my father had been tramping the country looking for work and had returned to learn of the family’s misfortune. Somehow he obtained a one room and brought the family home to it and there I joined them. Some while afterwards we were able to move to a house in Kimberley road Beckenham and things seemed a bit better.

Time passed and I got a little job for Saturday mornings, helping the gardener at a house in the more elite part of the Beckenham. I was paid sixpence and was given a meal consisting chiefly of any leftovers. My employer’s name was Mrs. Attenborough. She was a deed or of the women’s meeting that mother sometimes attended at Elm road Baptist church. She had visited us during my illness and was the lady responsible for my convalescence. As I approached school leaving-age she tried to discover what employment I would like to take up, but I hadn’t any ideas. Her family owned various pawnbrokers and jewellers shops in London and it was suggested that I entered one of these as an apprentice. I left school just before I was 14 and took up my first full-time post at a pawn-brokers in Southwark, a poor district. It lived in, was given my food and two and sixpence a week. I shared a room with two assistants older than myself who played upon my innocence to tell me all sorts of yarns and encouraged me to run away. During that week I learned about pawnbroking from the inside. Long before we were ready to open up the crowd of frowsy women would be banging at the door. It was my job to unbar the door and let them in, I was almost floored by the rush. That was the beginning of the week. All day long I would be clambering up and down racks storing the pledges away. At the week end it was the same job in reverse, finding each parcel that was redeemed. It was a gloomy shop with the store rooms above. I felt stifled. Sunday came and I got up early, pursed my few things, crept downstairs with my heart in my mouth, unbarred and unbolted the heavy door and fled. It was years later that I owned up to Mrs. Attenborough that the other lads were the principal cause of my flight. Now I was out of work after only one week and so was my father. However, this didn’t last long. I secured a post at a lovely old country house called Whitmore in Beckenham. I had to spend some time in the house shoes, Coles, windows, knives etc. And the rest of the day in the garden there are three men were employed. I was given breakfast and tea and two and sixpence a week. I was quite happy here my employer was an importer in the city, tea I believe. Those were the days of silk toppers and frock coats as everyday business wear. Beckenham was still only a quaint little village with a twisting high street and wooden shops. The surroundings were mainly large estates tenanted by wealthy people employing large staffs of servants. Five servants were employed at Whitmore’s. Mr. Ashton was my employer’s name. They were self-supporting in all garden produce and had their own farm with cows, pigs, chickens etc. It was here that I discovered a leaning towards mechanics. They had a heavy-duty Ransoms motor mower and this I found very interesting, especially when the under gardener, Will Thrainer, let me drive it occasionally. We all became a very good friend though he was much older. He was a Christian worker and his influence was good for me, he helped me in many ways.

All through my schooldays we had been taught to regard a war with Germany as inevitable, this despite the fact that our own royal family were of Teutonic descent and were related to Kaiser Wilhelm. In Nineteen-fourteen England was the richest and most powerful nation in the world, ¼ world’s surface came under British rule. Empire J May 24 was a weird letter day celebrated by the schools from all around marching to the Beckenham recreation ground, each pupil wearing a silken sash to distinguish them from other schools, each school had a different colour. At the recreation ground we formed up like a battalion of troops and in Unison sign patriotic songs, afterwards a march past the Union Jack and then the rest of the day off organised sports and a fireworks display at night. I remember the last Empire-Day, scorching hot and first aid people dishing out lemon and barley water to those overcome the heat. That was the last time that such celebrations were carried out. On August 4 war on Germany was declared. A great wave of patriotism swept the country. Lord Kitchener called for volunteers and there was no lack of response. Everyone thought the war would be over in three months. How mistaken day we were. My employer sent his two cars back to the makers to be taken care of and persuaded his chauffeur to enlist in the motor transport promising to credit his wages while he was serving in the forces. Whether he repented of this I do not know. Early in 1915 my father joined the horse transport o the Army Services Corps (In the Second World wat this was altered to Royal Army Services Corps). He was only in England a few weeks before being sent to the far east where he remained for five years, afterwards being invalided home. I think he was a nuisance to the authorities whilst in England because most weekends he came on leave and every Thursday a military escort called to take him back. The war dragged on and I began to be restless. I felt I should make a move so I left to take on a job as gardener’s boy at ten shillings a week and my tea. My employer this time was Mr Perkins, a large timber merchant who probably made a fortune from the war. At this place they had a Napier Landaulette and a chauffeur who further fostered my interest in things mechanical. I remember that car with its brass lamps and steel studded tyres. Eventually the chauffeur enlisted and I bought his bicycle for thirty shillings, quite a nice machine. After some months her, the gardener left to take up war work and I felt it was time I moved as well and so I secured a job at a small metal foundry. I forget what I was paid but I found the work interesting. The place was primitive, being a new venture and almost a back yard affair. I began to hear of the large earnings to be obtained at the Arsenal in Woolwich and so made application for a job there. I had an interview at the local labour exchange and was told to present myself at Woolwich Arsenal some time on a certain day. Before keeping the appointment I thought I would try a little blackmail on my present employers. I warned them of my proposed move to the Arsenal but intimated I would I would continue to work for them if they would increase my wages. Imagine my consternation when I was told politely that my conditions were unacceptable and they would dispense with my services.

Now I had been warned that to be late for the appointment at Woolwich would be fatal to my chances of being given employment there. Somehow or other I got delayed on the journey to Woolwich and arrived five minutes late so that was that and I was unemployed. Not for long though. The local Council needed men as most of the regulars had either enlisted or were on war-work. My elder brother by this time was in the forces. I lined up with others in the Council yard one morning while the foreman went along making his selection from the poor material present. I was told I could start as a dustman. I was a puny little chap, never fully recovered from my illness, and the work I was supposed to be able to do was to swing a heavy dustbin on to my shoulder, carry it out to the horse-drawn dust cart, mount a ladder at the side of this and expertly tip my bin of rubbish where it was supposed to go. Needless to say, I could not cope. My mate was having to do double the work. All I could manage was the horse, and this I enjoyed, feeling very proud as I handled the reins, though the horse did not need any guidance from me, it knew where to go alright. My next job was in the docks area of London, not far from Tower Bridge. I caught the two minutes past five a.m. train to London Bridge and then a tram along Tooly Street to arrive at the factory in time to start work at six o’clock. With a short break for meals I worked to nine for five days and to one o’clock on Saturday. I began my work in the warehouse where processed cereals were received via an elevator and chute from the mill and bagged up for loading onto waggons and despatch. Mainly food for the army stores. I was made a member of a gang on a printing machine, printing the firms’ name Uveco Cereals and a trade mark. The work turned out by the charge-hand on this was terrible, all smears and smudges. Eventually he left and I was given the task. I was so interested in the machine that I had excellent results and the foreman was very pleased and would have like me stay on that work. I had other ideas, separated from the warehouse by a narrow roadway was the mill, eight floors of machinery to be explored. Apparently the mill was disliked by the majority because of the heat and dust from the cereals and so I asked for a transfer. Naturally the warehouse foreman did not want to lose a good printer and was reluctant to let me go. However, I was determined and decided my printing had better deteriorate, which it quickly did. When the foreman realised that I had lost interest he let me go.

I now came under a Scotts foreman and it was decided that because of my evident interest I must learn every phase of the work, as eventually I did, I had better describe the process. First came the wharf on the river side, from here every activity on the Thames could be observed, with the frequent opening and closing of Tower Bridge to let ships pass under. Barges loaded with loose grain, wheat, maize etc. would be shunted by fussy little tugs to our wharf where the grain was loaded into sacks by piece workers and hoisted up and in by our electric lift or hoist and the sacks emptied into a hopper. From this hopper the grain, by means of travelling belts was passed through sieves to remove any thing foreign (all sorts of things) and then by elevators to silo bins eighty feet deep whence it was stored until the mill could deal with it. On the journey from the barge to the silo bins things could go wrong. A belt might come off stopping a conveyor or elevator with resulting confusion all along the bins. A careful watch had to be kept on everything. If the dockers had to stop unloading because of any machinery hold-up there was the dickens to pay. From the silo bins the grain travelled by conveyor bands and elevators to the mill when it was passed through heavy iron rollers, revolving at speed and making a frightful noise. Until I got used to the racket it was an unnerving experience to climb among the narrow plank galleries above the rollers to replace a belt or some other necessary task, or to work anywhere on that floor. After the grain had been crushed into flakes it was forwarded to the cooker floor where it would be steam treated and then to the driers where the moisture and dust were extracted and from here to the warehouse for sacking up and storing until required for despatch. At the age of sixteen I learned to control all this plant and my foreman never had to worry if he was late arriving I always started up all the machinery. Occasionally we stopped the mill for necessary maintenance and a rat hunt. Great was the slaughter on those occasions. One morning we arrived to find the area blocked by many fire engines. The adjoining biscuit factory (Spillers and Bakers) was on fire and our warehouse suffered damage from the Brigade hose pipes. However, they controlled the fire and then it was the task of cleaning and drying out before normal work could begin.

The War of course was still in progress and one night while in the darkened train, homeward bound, a terrific explosion shook the train and lit up the sky. A factory at Silvertown had gone up in fire and smoke. On a Saturday morning we had an air raid, the German planes followed the Thames to the docks and scattering bombs all around us. I stood on the fire escape near the top of our mill and had a grandstand view with no though of danger. It was a daring raid carried out in broad daylight and the first of the war.

(Before I go on with this reminiscence, I have just remembered that I have left out one of my jobs. From my dust cart I went to Muirheads, a large electrical firm mainly at that time engaged in the manufacture of wireless telegraphy for ships etc. I only stayed there about three months, giving up what might have developed into a wonderful career. Unfortunately, skylarking while working late one night got me into trouble and I was young and inexperienced and refused to be spoken to and so I left. It was from here that I went to the mill).

I stayed at the London job for about three months and enjoyed it every minute, though my mother insisted that I was killing myself I looked so pale and thin. I was not having nourishing food, mainly a bloater or bread and dripping from the local coffee shop and of course the long hours were not good for me as I was still not very strong. My reasons for leaving this job were quite different. I read an advertisement from the Royal Naval Air Service asking for volunteers prepared to fly in any type of aircraft or balloon and act as observers, ages 16 to 17. I made an application and went for an interview to Hotel Cecil on the Strand where I was directed to go to Wormwood Scrubs. Here I was to my great disappointment rejected on account of my deficient sight. This attempt to enlist caused me to be out of favour with the manager and foreman who were hoping I would accept exemption from service on the plea of essential war work. We had a few words about it and I left. Now I had to look for another job and when I saw an advertisement for a young man to learn to drive. I applied for and obtained the post. It was at Pelton Brothers [family grocers] at the Purley branch[1], now International Home Stores. Motoring was still in its infancy though on account of the war, developing fast. I had to learn to drive a model T type Ford van. No self-starter or windscreen in those days. My instructor was the shop manager, a poor teacher, but one who loved driving. I was slow learning because of his attitude but eventually I succeeded and felt at last I had the right job, fresh-air outdoor work delivering goods, a vocation entirely new and interesting. Since that day I have driven more motor vehicles than I can remember. During my service here I joined a section of volunteer motor transport, I was issued with a uniform and attended parades. What use we would have been in an emergency I have no idea. All we did was form fours. I drove the van and assisted in the shop, working very long hours and at Christmas time very often missed the last tram and had to walk back to Beckenham. However, I was really happy until early May 1918 I caught a bad dose of influenza. I had to stay away from work about a month. One day, feeling better, I went a short distance to see a friend. While I was away the manager called and would not believe my Mother when she told him this was my first outing since I had been taken ill. He had been told lies by my assistant who was assiduous to take on my job and had been informed by this chap that he had seen me about in Purley when all the time I was confined indoors. I was out of work again and although the truth emerged eventually it was too late to benefit me.

It was a difficult time to be unemployed as owing to the fact that I was approaching military age no one would give me employment. I tried to enlist, but on account of a new law recently passed they were not allowed to take me until I was eighteen. However, they did promise to forward my call-up papers by my birthday. This they did on the day. I had to report to Hounslow Depot where I spent one night. I was issued with kit and to satisfy the storeman’s sense of humour, or more likely because of his bad temper, I received a pair of size nine boots instead of sixes. The next morning in preparation for moving to our units we were divided and a one eyed and armed Sergeant-Major who shouted at me hardly able to walk in my size nines, that if I didn’t step out he would double me around the parade ground till I dropped. A very cheerful introduction to army life! Later that day in charge of an NCO we went by tube and train to Brockton camp, Stafford. In our new outfits of creased uniforms, without badge, we must have looked to the civilians absolute rookies, which of course we were, though I felt like a hero. We were at Brockton camp about four or five weeks, spent mainly square-bashing. We lived in huts and the food was not too bad, being cooked by members of the Women’s Army Auxiliary Force. I got my boots changed to size seven. One had to have a size larger than normal. Eventually we were drafted to Taverham Camp near Norwich where we lived under canvas. But before this move an epidemic of Spanish Flu swept the country and two third of the troops became casualties. All hospitals at Stafford and Cannock Chase became overcrowded. Huts were set aside for isolation and volunteers were requested to attend the sick. I was a volunteer and one day recovered consciousness to discover that I had nearly passed out myself. No medical aid was possible and I lay on my bed consisting of three planks until I recovered. [c. 48 hrs]

Arrived at Taverham we were allotted so many to a bell tent. I never thought we would find room to sleep but with all our feet to the centre pole we managed. We became stronger, more healthy-looking. The open-air life and physical training with regular if insufficient food was doing me a lot of good. We lost our pale complexions and assumed a healthy tan. At this camp training began in earnest. We did our field training, long route marches and fired our musketry and Lewis gun courses at both of which I excelled. In the autumn we moved to billets in Norwich from where we expected to be sent to France, but a recent act prohibited this until we had received our six months training. While at Norwich the armistice was signed. I remember we were at Norwich station unloading goods trucks when the news came. All was excitement and as we marched through the streets we received a great ovation though we had done nothing to win the war. After a short interval we were sent on leave, and then to France. We landed in Northern France and by goods trucks travelled through the battlefields of France and Belgium to Germany. Passing through Cologne and Bonn we arrived at Siegburg where we occupied a civil prison. Many of us were ill in this place, myself among them, but I never reported sick as I was scared of being accused of malingering. How I managed to soldier on I don’t know but somehow I did. Eventually we left the prison and were dispersed in small detachments in villages on the borders of the Saar [?]. Our unit went to a village named Weichied [?] and we occupied a derelict cottage sleeping on the floor. Life was better here. It turned out a glorious summer, very hot, and the surrounding countryside very lovely. I made friends of some of the Germans here and altogether was quite happy. We were employed on outpost duty enforcing the curfew and examining the credentials of travellers to and from the Saar area. All very farcical as none of us understood more than a few words of the language, though one could amuse themselves studying the women and the photographs on their pass. We stayed in Germany nine months until the Treaty of Versailles was signed and then returned to England using the same aids to travel as before (goods trucks) landing at Dover from Calais we entrained and travelled to Repton, Catterick Camp, Yorkshire.

My travels on the continent had been quite an experience. I had seen the battlefields or some of them and the devastation everywhere. I had seen how impoverished Germany had become as a result of the war and the effects of our naval blockade. I had visited Bonn and Cologne and see the former’s cathedral. I had travelled up the Rhine from Cologne to Coblenze [Koblenz ?] wher the Americans were the occupying troops. I had mounted guard in the Town Hall Square of Sieglung [Siegburg ?] with bands playing and much pomp and ceremony, the local populace as spectators. Now I was back in England, still a long way from home and looking forward to discharge. This was still some months away as quite rightly those who had born the brunt of the conflict were being released first. In the meantime a call came for two volunteers to go on a cooking course and believing that I should be sent South for this I made one, only to discover that we were to go to a school further North. We spent three weeks learning the culinary art and on returning to the unit was given the task of company cook. With one or two assistants I had to prepare meals for about three hundred men. The sergeant in charge of the cook-house was an ex-provost sergeant (Police) and he treated me as though I was a convict, nothing was right for him. One day the orderly officer in his presence asked me how I liked the cook house. I told him I hated it and the reason why. After that things were done better and I became personally content. By this time my father and elder brother had returned to civil life. My father wrote to me advising that I sign on as things were so bad. We were offered a stripe and fifty pounds to sign on for a further five years. Much had been said during the war about men returning to a land fit for heroes, instead they returned to chaos and mass unemployment. When I finally came home it was to find that my father was the only one employed. However, I had to wait for my discharge before I saw how bad things really were. On the day of my release an officer led a party of us to the station to catch the train. As we marched behind him we sang ‘A little child shall lead them’. Things improved in the building trade and my father was able to get jobs with him for my brothers, but he refused to take me contending that I was not strong enough.

I was unemployed for seventeen months, drawing a pittance from the labour exchange with which I had to pay something for my keep and try to re-fit myself with clothes so very necessary after my two years’ service. I managed about two weeks work for a greengrocer looking after his horses and assisting on a round, but I was not much use on this job and so it ended. My father relented at last and took me to work on some public works at Roehampton, making roads and laying down drains for a new housing estate. I will not forget the kindness of the foreman on that job who realising that I was trying but suffering did what he could to make things easier. The first day was agony. I got used to it though and worked for them for some months earning quite good money. In the end I left and went to work on the Beckenham Housing Scheme as a bricklayer’s labourer. I got on very well here and the general foreman wanted me to train as a bricklayer but I could not afford to drop down to apprentice rates. Eventually this job was finished and we all got the sack. My father had got a job widening a road at Edenbank and I became one of his gang, working on the road and when required doing Father’s office work. The last task I carried out was to stamp the men’s cards at the end of the job and then give myself the sack. We had now reached the parting of the ways. I was engaged to be married and I knew that I had to do something to get myself out of the building trade, otherwise I would be a labourer all my life.

I approached the Government for a training grant in motor engineering and this was granted, but the conditions attached made it impossible for any employer to take me on as he would have to guarantee my employment when the training finished. This was an impossible condition as no one could know until I had finished my training what aptitude I had for the work. So this door was closed. However, I was determined not to return to labouring in the building trade and eventually got a job with Olbys of Penge, Builders Merchants, driving a one-ton lorry. This was a rough job and poorly paid. Olby’s took full advantage of the condition of the labour market and set me impossible tasks. Such as unloading a heavy iron kitchen-range by myself and if I could not manage it telling me to stop someone in the street and give them threepence to help me. One day I lost my temper and threw caution to the winds. I told him what I thought of him and what he was. It took him two weeks before he gave me the sack and then assured me it was not because of what I had said to him. Again I was unemployed.

I got a job at a firm of contractors at Upper Norwood where I was engaged to drive another one-ton Ford. They also had two heavy lorries and a charabanc. I drove them all in time. They were the local contractors for the Royal Mail which they carried out with a horse-drawn vehicle. Everyone was becoming motor-minded and the Post Office were no exception. My firm had to supply a van instead of a horse and I became the Royal Mail driver. I stayed in this job until I saw an opportunity to improve my wages with a firm of dyers and cleaners. This firm was in its infancy beginning in a small way by renovating ladies and gents’ hats, afterwards expanding to take on the whole range of dying and cleaning. I stayed with this firm quite a while helping them over quite a few difficulties and once leaving them some of my savings to pay wages. In the end they turned into a public company and after disagreement with the Traveller I left. All the time I had been learning something and my knowledge of how the motor car functioned increased. As I had left before finding another job. I needed to find a stop-gap and this did not take long. I went as a van driver for a motor accessory firm, only a small business. They would have liked me to continue in their employ but the wages were not good enough. After a while I was engaged as a chauffeur–handyman by a retired journalist and held this post for fifteen years until the beginning of the Second World War. I had quite a bit to tolerate at this place. More and more responsibilities were heaped upon my shoulders while the unmarried daughters could be very demanding at times. Times were still very difficult and as I was now a married man, I had to control my natural independence. My employer had five daughters, two still at home and his two sons were killed in the First World War. Gradually he became more and more dependent on my abilities and when his wife died I took over his personal care and any secretarial work that was needed. He died in a nursing home a few months after the outbreak of the 2nd World War.

Great Britain declared war n Germany on September 3rd 1939. My people fled to Reigate where they thought they might be safer from the expected air raids. They returned after a while but not before I had arranged for a massive air-raid shelter in the garden. I left and joined the Auxiliary Fire Service but soon sickened of this as it was mainly staffed by scroungers who hoped to avoid military service. I left this and joined the recently formed Defence Volunteers, afterwards named the Home Guard, and left this to join the forces. But before my enlistment I spent a short while at an Air Ministry maintenance unit. Afterwards I secured employment in a local emergency factory where my natural aptitude for things mechanical gained me early recognition and I became the milling machine setter and operator carrying out work to very fine limits and grinding my own cutters – quite a skilled operation. I did not like the inside work and longed to be out in the fresh air. I succeeded in getting permission to join the forces and finally enlisted in the Royal Army Service Corps. This took me first of all to Chesterfield in Derbyshire where we did a month or so of square bashing and small arms training. All this I found easy benefitting from my previous army training in the 1914-18 war. Our next move was to Sheffield for driving and mechanical instruction. I quickly passed the driving test but had to retire to hospital for a hernia operation, afterwards to a convalescent home in Sheffield and then to Halifax for remedial exercises. With one week’s leave this had occupied three months of my service.

After returning to my unit I found all my pals had moved on and I was among strangers. I took a day off to get used to things. No one missed me. I then passed a trade test as a fitter and was sent to workshops in Sheffield. Signs and portents convinced me that the invasion of the continent was not far away and I was due for leave. It was expected that all leave would be stopped. I was lucky my leave was granted and my Sergeant-Major advised me to go that night. I went, arriving in London just before leave was cancelled and about half an hour before the military police received orders to turn anyone back to their units. I had fourteen days at home while others were being recalled to stations. On my return I applied for a field posting. This cannot be refused and although those in authority at my unit did their best to persuade me to stay, I persisted with my request. That unit never left England. I went to a holding [?] company and from there to Oundle in Northumberland where I arrived exhausted after travelling all day without food. There I joined 3 Company RASC just returned from the desert and 8th Army. It was Saturday night when I joined them and on the following Monday morning we were in convey en route for the South coast and Littlehampton, where we arrived after a couple of days. From here. After spending a week at Southwick bivouacked in a field close to Eisenhower’s headquarters. Half the company left for France while my party went to London and Tilbury Docks. I spent one night sleeping by the roadside under a tarpaulin while doodlebugs passed overhead. We boarded ship with our vehicles and lay off Southend for about a week, bored stiff. Finally we moved and at night hugging the English coast we crept through the Straits of Dover and fetched up South of the I.O.W. From there we sailed a mass of vessels to the French coast and transferring into landing barges we went ashore.

As this is not a war story I will simply say that we proceeded through Belgium and Holland to Hamburg in Germany. Before this happened I spent a weekend leave in Paris and afterwards went there on detachment for about six weeks. I finally was given a week’s leave and whilst at home the Armistice was concluded. I returned and learned that we were going to Norway and this country we soon embarked for, travelling on American tank [?] landing craft escorted by naval corvettes. We left the devastation of Hamburg and sailing up the Elber, crossed the Skagerrak and reached the coast of Norway. We proceeded through the fiords leaving detachments at Oslo, Bergen, Stavanger and Christiansands [Kristiansund ?] finally arriving at Trondheim which was to be Company HQ. It had been a marvellous trip with wonderful scenery.

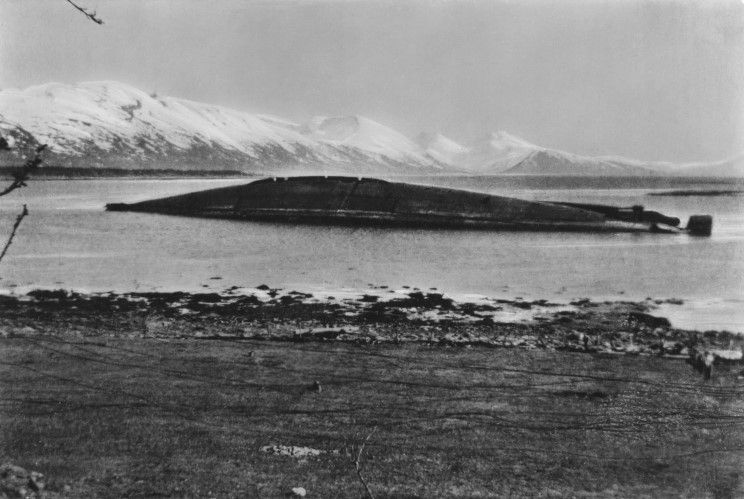

It was June and the nights never got dark as we were so far north. Finally I was sent on detachment with three others and after five days and nights of cruising among the Lofoten Islands we reached Tromso, 300 miles north of the arctic circle. It was a wonderful experience here to see the sun shining day and night and this continued to the autumn when we were treated to wonderful displays of northern lights and marvellous coloured skies. Whilst here we took trips to the mainland across the ferry [?] and aquiring a boat with a powerful outboard engine did some boating around the islands. We sailed to where the battleship Turpitz lay upside down in ? Fiord, its guns and superstructure in the sea bed and the ship’s bottom above the surface. We climbed aboard and walked along the bottom of this great ship.

Winter came with it snow and ice. We used [a] Chevrolet with four-wheel drive so could get about but the civilians used horse sleighs with bells tinkling, or pushchairs on runners which they used like scooters. We were due to return to Trondheim as all troops were to hand over the country to the Norwegians. But first of all we had to wait for a ship. Eventually we secured an old tramp steamer and this took us back. The ship was covered in ice everywhere and walking on the iron decks was dangerous. Soon after reaching Trondheim we boarded the SS Bamford for Leith in Scotland. We had a stormy passage and were two and a half days at sea. I was very sea-sick. On reaching Leith we entrained for Cardiff, S. Wales. I was detached to Newport and from there to the I.o.W. After several months I went to Guildford for my discharge. So ended that adventure.

Now I had the problem of finding work which I obtained as chauffeur to a rich waste-paper merchant. I did not enjoy working for him. He was fond of drink and kept me very late in town at night while he was enjoying himself. I had made application of a petrol ration in order to start a hire service and this was granted. I left the waste-paper merchant and with the assistance of a loan from my late employer’s daughter I bought my first car – afterwards several more. I secured the station rights at Coulsdon South station and through various ups and downs made progress and was able to repay the loan. I sold the business and using a taxi only made a good living until I retired in 1965 and here I am now 70 years young pleasing myself what I do.

PS I should have mentioned that in 1918 my service was with the Bedfordshire Regiment, afterwards named the Beds and Herts and was for nearly two years. In the RASC I served three years.