Behind the Victorian Fountain at the entrance to Botley Railway Station (so called – it is of course in Curdridge) there is a cast iron plaque mounted on cemented stones :

It reads :

This Stone is Erected to Perpetuate a Most Cruel Murder Commited on the Body of Thomas Webb a Poor Inhabitant of Swanmore on the 11th of February 1800 By John Diggins a Private Soldier in the Talbot Fencibles Whose remains are Gibbited on the adjoining Common

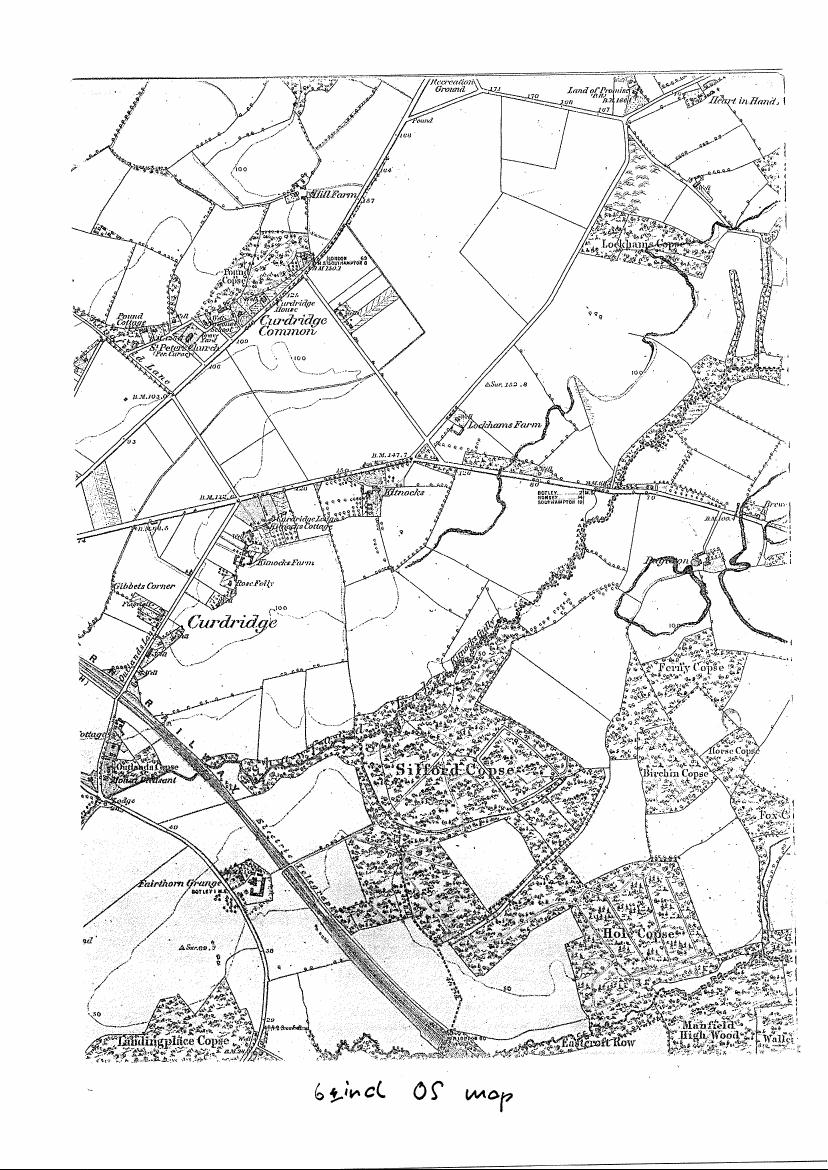

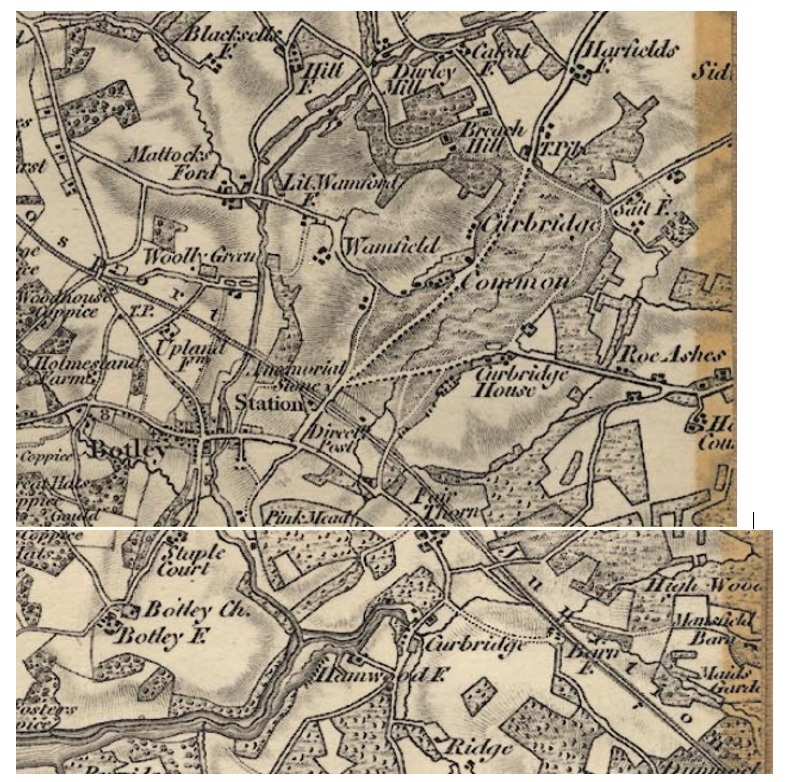

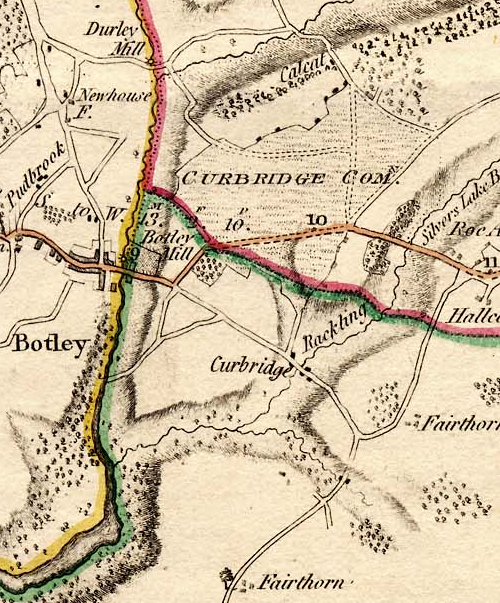

The Talbot – or Tarbet – Fencibles were barracked in Botley at the time. Private Diggins, with two other soldiers, had come upon Thomas Webb, a poor and elderly pedlar, somewhere near Kings Corner (Pinkmead) in Curdridge. They not only robbed him of what few shillings he had, but then – according to a contemporary newspaper report – stabbed him, threw him in a ditch and stamped on him. Despite his injuries, Webb was able to crawl to a nearby cottage and get help – including the removal from his body of six inches of bayonet by a local surgeon. He was also able to tell what had happened – before he died. Diggins was found guilty of the murder at Winchester Assizes and sentenced to be hanged. The other two soldiers were acquitted for lack of evidence. Diggins was hanged in Winchester and his body then gibbited – that is, hung to rot – on Curdridge Common, between the main road to Shedfield and Outlands Lane. Thomas Webb was buried in St Peter’s Church graveyard, Bishops Waltham.

Meanwhile, the stone referred to on the plaque is not the cemented stones on which the plaque itself is mounted, but the undistinguished stone, without inscription, which sits half buried behind it. This suggests that the plaque was a later addition, Victorian perhaps, by when local history had became a subject of much interest.

All this can be found in more detail in local historian Dennis Stokes’ Botley and Curdridge – A history of two Hampshire villages, published by the Botley and Curdridge Local History Society (2007) – http://www.botley.com/history-society

I became curious about the plaque when I came upon the following:

Hampshire Treasures, Volume 1 ( Winchester City District), Page 82 – Curdridge

| Memorial Stone |

Site of murder. Culprit hanged on local gibbet, cast iron plaque removed to Portsmouth City Museum. |

|

|

SU 520 130

1904 27 |

How can the plaque have been ‘removed’ to Portsmouth and yet still be present in Curdridge ?

I wrote to the Museum about it. Their reply was :

“The original plaque was donated to the Portsmouth City Museum before 1945 & is kept in storage there, although it has been used in a display at Southsea Castle. The plaque at Botley Station, therefore, must be a copy.”

Our plaque a copy ? Why, that practically makes it a forgery !

Or, perhaps, for some reason, two copies of the plaque were made at the same time? But why ?

History, it seems, is full of mystery . . .

Still, if anyone knows anything more about this matter, do let me know.

*

*

And yet another, brought to my attention by Rob Jeffries (see below) :

The Cruise of the Land-Yacht “Wanderer”; or Thirteen Hundred Miles In My Caravan, by William Gordon Stables, London 1892.

Extract from Chapter Twenty Seven.

Botley is one of the quietest, quaintest, and most unsophisticated wee villages ever the Wanderer rolled into . . . My attention was attracted to a large iron-lettered slab that hangs on the wall of the coffee-room of the Dolphin. The following is the inscription thereon:—

This Stone is Erected To Perpetuate a

Most Cruel Murder Committed on the Body

of Thos. Webb a Poor Inhabitant of Swanmore

on the 11th of Feb. 1800 by John Diggins

a Private Soldier in the Talbot Fencibles

Whose Remains are Gibbeted on the Adjoining Common.

And there doubtless John Diggins‟ body swung, and there his bones bleached and rattled till they fell asunder.

But the strange part of the story now has to be told; they had hanged the wrong man!

It is an ugly story altogether. Thus: two men (Fencibles) were drinking at a public-house, and going homewards late made a vow to murder the first man they met. Cruelly did they keep this vow, for an old man they encountered was at once put to the bayonet. Before going away from the body, however, the soldier who had done the deed managed to exchange bayonets with Diggins. The blood-stained instrument was therefore found in his scabbard, and he was tried and hanged. The real murderer confessed his crime twenty-one years afterwards, when on his deathbed.

So much for the Botley of long ago.

The iron slab, by the way, was found in the cellar of the Dolphin, and the flag of the Talbot Fencibles, strange to say, was found in the roof.

and the lion :

and the lion :

This story tells of a young woman who drowned one night on Kitnocks Hill while trying to elope. I have written about this affair previously in the Parish News (see:

This story tells of a young woman who drowned one night on Kitnocks Hill while trying to elope. I have written about this affair previously in the Parish News (see: